***(Insert

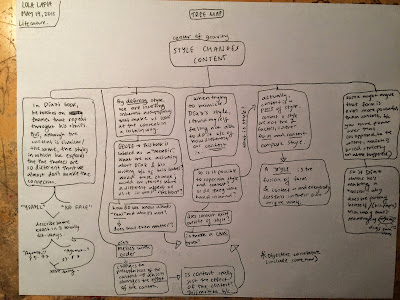

somewhere) Writing is typically composed of two essential factors or

components: style and content. The content is the facts, the material, what

actually happened, while the style is the medium, the approach, the technique.

In

Junot Diaz’s Drown, he writes ten different short stories whose various

themes range from family crisis to betrayed

love. Each story appears to have its own plot, its own characters, its own

narrator: from “Fiesta, 1980,” which revolves around the tension of family and

how enhanced that becomes at family gatherings, to “Aurora,” all about a young

man’s yearning for a girl in the midst of drugs and vandalism. Not only do his

stories shift in content, but Diaz also uses a multitude writing styles that

change from story to story, even page to page: poetic sophistication, intimacy

with the reader, the use of objective correlatives, and many more.

Yet,

only once we look deeper do we see traces of the same themes pop up in each

story. We notice many recurring characters, similar issues, and similar emotions that it seems Diaz is actually tackling the same

themes and issues throughout the whole of his book. But although the content is

often the same in all of Diaz’s stories,

the styles in which he explores and navigates the content greatly vary, so much

so that we almost miss the connection. In addition, his format of short stories

would lead us to initially think that each one stands on its own, yet when thoroughly

investigated it seems that they’re in fact related. So if Diaz’s styles are so

numerous and varied, yet the stories seem to thematically connect, what is the

relationship between his style and his content? How do they relate to each

other, depend on each other, work together?

One

way to consider this is to see that these stories really aren’t isolated from

one another, but each one a distinct method or lens that Diaz uses to reflect

on and explore the journey of a young boy, Yunior, and his encounters,

experiences, challenges, and more over the course of his early life.

Furthermore, Diaz’s his wistful form and serious content are so inextricable

and intimately intertwined that isn’t possible to disconnect the two, but only

to acknowledge and embrace them as one. Evidently, it is not style and content

that coexist but rather form and

content that fuse together to form a style. Thus, Diaz embodies many styles in

his book, because as his form changes from story to story, so does his style. He

uses the power of form by using poetry, metaphors, analogies and more to weave

together a tale so intricately layered with thoughts and emotions and experiences.

So rather than trying to pinpoint or label Diaz’s style, it is more effective

to observe and analyze his writing as a whole, and explore how he

idiosyncratically integrates his content and his form to reveal and present his

stories.

First

and foremost, Diaz’s way of introducing details alters our reactions and

interpretations of the events within the stories. He has a consistent style of

messing with the order of revealing information, both with the order of the

stories themselves, and even within the actual stories. In the 2nd chapter “Fiesta,

1980,” he welcomes us into the book by informing us of Yunior’s familial

situation in America, and their relationship with their father. So when we read

“Aguantando” at the very end of the book and we go back in time to learn about

the family’s journey of getting to America, it makes it all the more heartbreaking to see their family

all as one when we know they’ve had all those bumps in the road....

Diaz’s

style, if one were to try to name it, is like a chameleon.

Diaz

has a way of using seemingly unimportant, everyday details to represent

something much deeper (pool table, gingko tree in “Edison, New Jersey”).

Objective

correlatives are a prime example of how not only are Diaz’s form and content

inseperable, but his form actually effects the content.

Diaz’s

ever changing form continues to alter his content in “Ysrael” and “No Face.”

Something

interesting also enters the picture when we define

style, which is most commonly done by using the idea of genres to classify

writing. Because this book is labeled as a “memoir,” we are making instant

assumptions about the story, and about Diaz himself. But would it change our

reading of the text if it was “fiction,” per se? The effect of the stories on

the readers would change, and maybe even alter our interpretation on the

content and messages of the literature. As Edna St. Vincent Millay said in

1925, “A person who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with

his pants down.” When sharing any of their writing with the public, authors put

themselves at stake for judgment and critique by their audience. And a book is

most reflective of the author–or at least we assume so–when it is labeled as a

memoir. So as readers, all the experiences that we see Yunior going through, we

assume they come directly from Diaz’s life. But how is it fair to place a

bounding, limiting box onto Diaz and his abilities as an author? Diaz could

very well be exaggerating things, expanding on things, adding things to help

create a sort of mood or affect. But does that break the rules and requirements

of a “memoir”? Many would argue that it does. And this shows how tricky and

restrictive it can be to place a name or category onto a style.

Diaz

also blurs the line between fiction and the real when he uses fantasy as a way

to reveal information about the characters and there emotions (Aguantando

fantasy moment).

Diaz

claims he wants to “make some mirrors so kids like [him] might see themselves

reflected back.” Although he has the power to create this “mirror,” he portrays

himself and people like him in a way that’s seemingly negative, what with

drugs, intense family issues and scandals, and other things that would seem to

reflect poorly on his culture. But maybe this is the truth. This is his life;

this is not a peace of fiction that tries to artificially represent a group of

people. Diaz is raw, honest, and truthful, but also poetic, lyrical, and

intimate. He uses the power of style not to alter and hide the truth, but to

embrace it and get in touch with its reality.

So

really, in Diaz’s book there is no raw truth. There are no stripped down, naked

facts. There is only what he gives us, which is his own spin on the truth. But

is it reliable? Is it the truth? Can

content exist outside of style? Everybody, every author, every person, tells

their tale in their own unique way. But no matter who claims they have unbiased

information, direct records, or the truth,

everything we’ll ever see of anything will always have some sort of spin on it.

So what can we call the truth? Did his dad really abandon his family the way

Yunior claims he did? Did his mom really disappear for a while for the reasons

Yunior claims she did? Will we ever know? Does it even matter? We have to treat

his story as his own, personal truth. (Does the way Diaz/Yunior write about the

events in his life affect our take away from the stories? Of course.)