During 5th period of Symposium Day today, I went to the session, "What I Should've Said: Poetry Collections," of which Mr. Garces Kiley was the faculty advisor. Six Year 2 girls, who had all both taken Mr. Kiley's poetry workshop and/or did poetry with him as their independent study this semester, read a collection of their poems aloud, and briefly explained their motives and feelings behind each poem.

But to be honest, what interested me more then the poetry itself was the panel discussion that the girls had after presenting. It was wonderful to hear about how much poetry meant to each of them even beyond it being initiated in the realm of school and required work. One girl, I remember, mentioned how poetry is sort of "theraputic" for her, which I've felt before and I think is such a wonderful idea. It almost matters less what the poem is actually saying, but how the poem is a particular way of channelling and expressing emotions, and how each girl used their poems as outlets of expression. Often students do work for school because it's required, but it was so refreshing to see the genuine interest that all these girls had in poetry and in learning more about themselves through writing poetry.

What's special about a poem is that it's often very vague. And because us readers often don't know what's really going on, or what exact experience the poet is honing in too, the poem actually says more about the poet him/her self that about the actual content. This was really evident in the presentation because we got to here from six very different poets. The girls mentioned how when workshopping with each other, they really noticed how they each had really distinct styles, more so then they would've expected. And that was even clear when they were presenting. They each used the poetic form to express something different, to channel in on their own feelings, to explore the past, the present, and a year of nostalgia.

It was really a great presentation, and I would love to take the poetry course that they all did when I'm a Year 1/2.

Lola's Literature of the Americas Blog

Friday, June 5, 2015

Thursday, May 28, 2015

3rd Draft of Style Essay

***(Insert

somewhere) Writing is typically composed of two essential factors or

components: style and content. The content is the facts, the material, what

actually happened, while the style is the medium, the approach, the technique.

In

Junot Diaz’s Drown, he writes ten different short stories whose various

themes range from family crisis to betrayed

love. Each story appears to have its own plot, its own characters, its own

narrator: from “Fiesta, 1980,” which revolves around the tension of family and

how enhanced that becomes at family gatherings, to “Aurora,” all about a young

man’s yearning for a girl in the midst of drugs and vandalism. Not only do his

stories shift in content, but Diaz also uses a multitude writing styles that

change from story to story, even page to page: poetic sophistication, intimacy

with the reader, the use of objective correlatives, and many more.

Yet,

only once we look deeper do we see traces of the same themes pop up in each

story. We notice many recurring characters, similar issues, and similar emotions that it seems Diaz is actually tackling the same

themes and issues throughout the whole of his book. But although the content is

often the same in all of Diaz’s stories,

the styles in which he explores and navigates the content greatly vary, so much

so that we almost miss the connection. In addition, his format of short stories

would lead us to initially think that each one stands on its own, yet when thoroughly

investigated it seems that they’re in fact related. So if Diaz’s styles are so

numerous and varied, yet the stories seem to thematically connect, what is the

relationship between his style and his content? How do they relate to each

other, depend on each other, work together?

One

way to consider this is to see that these stories really aren’t isolated from

one another, but each one a distinct method or lens that Diaz uses to reflect

on and explore the journey of a young boy, Yunior, and his encounters,

experiences, challenges, and more over the course of his early life.

Furthermore, Diaz’s his wistful form and serious content are so inextricable

and intimately intertwined that isn’t possible to disconnect the two, but only

to acknowledge and embrace them as one. Evidently, it is not style and content

that coexist but rather form and

content that fuse together to form a style. Thus, Diaz embodies many styles in

his book, because as his form changes from story to story, so does his style. He

uses the power of form by using poetry, metaphors, analogies and more to weave

together a tale so intricately layered with thoughts and emotions and experiences.

So rather than trying to pinpoint or label Diaz’s style, it is more effective

to observe and analyze his writing as a whole, and explore how he

idiosyncratically integrates his content and his form to reveal and present his

stories.

First

and foremost, Diaz’s way of introducing details alters our reactions and

interpretations of the events within the stories. He has a consistent style of

messing with the order of revealing information, both with the order of the

stories themselves, and even within the actual stories. In the 2nd chapter “Fiesta,

1980,” he welcomes us into the book by informing us of Yunior’s familial

situation in America, and their relationship with their father. So when we read

“Aguantando” at the very end of the book and we go back in time to learn about

the family’s journey of getting to America, it makes it all the more heartbreaking to see their family

all as one when we know they’ve had all those bumps in the road....

Diaz’s

style, if one were to try to name it, is like a chameleon.

Diaz

has a way of using seemingly unimportant, everyday details to represent

something much deeper (pool table, gingko tree in “Edison, New Jersey”).

Objective

correlatives are a prime example of how not only are Diaz’s form and content

inseperable, but his form actually effects the content.

Diaz’s

ever changing form continues to alter his content in “Ysrael” and “No Face.”

Something

interesting also enters the picture when we define

style, which is most commonly done by using the idea of genres to classify

writing. Because this book is labeled as a “memoir,” we are making instant

assumptions about the story, and about Diaz himself. But would it change our

reading of the text if it was “fiction,” per se? The effect of the stories on

the readers would change, and maybe even alter our interpretation on the

content and messages of the literature. As Edna St. Vincent Millay said in

1925, “A person who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with

his pants down.” When sharing any of their writing with the public, authors put

themselves at stake for judgment and critique by their audience. And a book is

most reflective of the author–or at least we assume so–when it is labeled as a

memoir. So as readers, all the experiences that we see Yunior going through, we

assume they come directly from Diaz’s life. But how is it fair to place a

bounding, limiting box onto Diaz and his abilities as an author? Diaz could

very well be exaggerating things, expanding on things, adding things to help

create a sort of mood or affect. But does that break the rules and requirements

of a “memoir”? Many would argue that it does. And this shows how tricky and

restrictive it can be to place a name or category onto a style.

Diaz

also blurs the line between fiction and the real when he uses fantasy as a way

to reveal information about the characters and there emotions (Aguantando

fantasy moment).

Diaz

claims he wants to “make some mirrors so kids like [him] might see themselves

reflected back.” Although he has the power to create this “mirror,” he portrays

himself and people like him in a way that’s seemingly negative, what with

drugs, intense family issues and scandals, and other things that would seem to

reflect poorly on his culture. But maybe this is the truth. This is his life;

this is not a peace of fiction that tries to artificially represent a group of

people. Diaz is raw, honest, and truthful, but also poetic, lyrical, and

intimate. He uses the power of style not to alter and hide the truth, but to

embrace it and get in touch with its reality.

So

really, in Diaz’s book there is no raw truth. There are no stripped down, naked

facts. There is only what he gives us, which is his own spin on the truth. But

is it reliable? Is it the truth? Can

content exist outside of style? Everybody, every author, every person, tells

their tale in their own unique way. But no matter who claims they have unbiased

information, direct records, or the truth,

everything we’ll ever see of anything will always have some sort of spin on it.

So what can we call the truth? Did his dad really abandon his family the way

Yunior claims he did? Did his mom really disappear for a while for the reasons

Yunior claims she did? Will we ever know? Does it even matter? We have to treat

his story as his own, personal truth. (Does the way Diaz/Yunior write about the

events in his life affect our take away from the stories? Of course.)

Monday, May 25, 2015

2nd Draft of Style Essay

For the radical revisions, I worked a lot on my claim, and also my introduction as a whole. I also tried to generate some missing text in some parts, and now know what I have to do to generate the missing text for the rest of my essay.

-

-

Writing

is typically composed of two essential factors or components: style and

content. The content is the facts, the material, what actually happened, while

the style is the medium, the approach, the technique.

In

Junot Diaz’s Drown, he tackles the

same themes and issues throughout his story. Yet the ways in which he explores

and navigates them greatly vary from story to story, even page to page. So although

the content is the same in many parts of the book, the styles in which the

content is relayed are so different that we almost miss the connection. And

furthermore, when trying to extract his style in order to replicate and mimick

it, it became seemingly impossible to separate it from the content. It seemed

almost as if they were combined, So what is the relationship between style and

content? How do they relate to each other, depend on each other, work together?

Content

is a part of style. It is not style and content that coexist but rather form and content that fuse together to

form a style. In Diaz’s novel, his form and his content are so inextricable and

intimately intertwined that isn’t possible to disconnect the two, but only to

acknowledge and embrace them as one. Furthermore, it is not just one distinct style that Diaz embodies in

his book, but many. He uses the power of poetry, metaphors, analogies, and more

to weave together a tale so intricately layered with thoughts and emotions and

experiences. Rather than trying to pinpoint or label Diaz’s style, it is more

effective to observe and analyze his writing as a whole, and explore how he

idiosyncratically integrates his content and his form to reveal and present his

stories.

In

Diaz’s book, he explores similar themes repeatedly throughout his story. But

although the content is similar/even the same, the styles in which he explores

the themes are so different that we almost don’t make the connection. So the

way he tackles his themes hugely affects the content of the story: or at least,

it affects the effect of the content. The very first chapter of the story,

“Ysrael,” revolves around Yunior and Rafa’s encounter with Ysrael, the boy

who’s face was scratched and destroyed by a pig when he was very young, as he

describes to the reader while he watches Rafa beat Ysrael up. Eight stories

later in “No Face, we read about a boy who always wears a mask to cover up his

face. And halfway into the chapter, when we start to make the connection from

story to story, Diaz, or rather the narrator, gives us a different description

of the same event from “Ysrael.” Although the content is the same, the styles

in which the content is relayed are so different that we almost miss the

connection. (***go further

deeper

into each of the styles.)

Something

interesting also enters the picture when we define

style, which is most commonly done by using the idea of genres to classify

writing. Because this book is labeled as a “memoir,” we are making instant

assumptions about the story, and about Diaz himself. But would it change our

reading of the text if it was “fiction,” per se? The effect of the stories on

the readers would change, and maybe even alter our interpretation on the

content and messages of the literature. As Edna St. Vincent Millay said in

1925, “A person who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with

his pants down.” When sharing any of their writing with the public, authors put

themselves at stake for judgment and critique by their audience. And a book is

most reflective of the author–or at least we assume so–when it is labeled as a

memoir. So as readers, all the experiences that we see Yunior going through, we

assume they come directly from Diaz’s life. But how is it fair to place a

bounding, limiting box onto Diaz and his abilities as an author? Diaz could

very well be exaggerating things, expanding on things, adding things to help

create a sort of mood or affect. But does that break the rules and requirements

of a “memoir”? Many would argue that it does. And this shows how tricky and

restrictive it can be to place a name or category onto a style.

Writers

often run into difficulty when trying to mimic styles. When we were told to use

Diaz’s style to write our own creative pieces, I found myself hesitant and

confused out of the fear that it wouldn’t work because our content was so

different. My story had none of the heartbreak, family drama, or immigration

struggles that Diaz’s stories tackle, and I found it nearly impossible to

separate his style, his way of writing, from his pure content.

Diaz’s

way of introducing details alters our reactions and interpretations of the

events within the stories. He has a consistent style of messing with the order

of revealing information, both with the order of the stories themselves, and

even within the actual stories. In the 2nd chapter “Fiesta, 1980,” he welcomes us

into the book by informing us of Yunior’s familial situation in America, and

their relationship with their father. So when we read “Aguantando” at the very

end of the book and we go back in time to learn about the family’s journey of

getting to America, it makes it

all the more heartbreaking to see their family all as one when we know they’ve

had all those bumps in the road....

Diaz

claims he wants to “make some mirrors so kids like [him] might see themselves

reflected back.” Although he has the power to create this “mirror,” he portrays

himself and people like him in a way that’s seemingly negative, what with

drugs, intense family issues and scandals, and other things that would seem to

reflect poorly on his culture. But maybe this is the truth. This is his life;

this is not a peace of fiction that tries to artificially represent a group of

people. Diaz is raw, honest, and truthful, but also poetic, lyrical, and

intimate. He uses the power of style not to alter and hide the truth, but to

embrace it and get in touch with its reality.

Definitiely explore more how form changes content.

In

Diaz’s book there is no raw truth. There are no stripped down, naked facts.

There is only what he gives us, which is his own spin on the truth. But is it

reliable? Is it the truth? Can

content exist outside of style? Everybody, every author, every person, tells

their tale in their own unique way. But no matter who claims they have unbiased

information, direct records, or the truth,

everything we’ll ever see of anything will always have some sort of spin on it.

So what can we call the truth? Did his dad really abandon his family the way

Yunior claims he did? Did his mom really disappear for a while for the reasons

Yunior claims she did? Will we ever know? Does it even matter? We have to treat

his story as his own, personal truth. Does the way Diaz/Yunior write about the

events in his life affect our take away from the stories? Of course.

Explore

more some of the actual “forms” that Diaz uses (objective correlatives,

metaphors, poetry, fantasy).

Friday, May 22, 2015

Letter to Riya

Dear Riya,

After reading your first draft, it seems that your center of gravity is that Diaz writes in this messy, unique, intricate, non-traditional style because by doing so, he is able to create intimacy and empathy with his readers. You argue that Diaz wants readers to connect to the characters, and does so by forcing us to "place ourselves into the character's shoes." You have a fascinating idea that because we readers have to take the vague, indirect details that Diaz gives us and piece them together ourselves, that in turn makes the story more personal.

You have a very strong claim, and are on your way to finding some great evidence and support. I want to know more about how we are able to "step into the narrators shoes," as you say. You give some descriptions in your claim, but I want more details, more contextual evidence. One interesting idea that we talked about in class that you could expand on is how Diaz, although he knows what will happen in every chapter because he's lived these stories, still writes as if he's experiencing the story in the moment; he writes as if he's reliving it. Why is that? Maybe he wants his readers to experience the events and feel the emotions just as he did in the moment. He creates this intimacy, this closeness, as if he wants the reader to be his friend, be on his level, if that makes sense. Like we said in class, he seems to recreate the relationship between the author and the reader, in a way that greatly strays away from the traditional role of the author in most stories. Maybe how he writes in first person could be evidence for this.

I would say the big thing for you to go deeper in now is how Diaz does all these things. You have strong start with evidence, but I think you need to go further with "how." Otherwise, just add more evidence, finish your body paragraphs, and you're set! Great work.

-Lola

After reading your first draft, it seems that your center of gravity is that Diaz writes in this messy, unique, intricate, non-traditional style because by doing so, he is able to create intimacy and empathy with his readers. You argue that Diaz wants readers to connect to the characters, and does so by forcing us to "place ourselves into the character's shoes." You have a fascinating idea that because we readers have to take the vague, indirect details that Diaz gives us and piece them together ourselves, that in turn makes the story more personal.

You have a very strong claim, and are on your way to finding some great evidence and support. I want to know more about how we are able to "step into the narrators shoes," as you say. You give some descriptions in your claim, but I want more details, more contextual evidence. One interesting idea that we talked about in class that you could expand on is how Diaz, although he knows what will happen in every chapter because he's lived these stories, still writes as if he's experiencing the story in the moment; he writes as if he's reliving it. Why is that? Maybe he wants his readers to experience the events and feel the emotions just as he did in the moment. He creates this intimacy, this closeness, as if he wants the reader to be his friend, be on his level, if that makes sense. Like we said in class, he seems to recreate the relationship between the author and the reader, in a way that greatly strays away from the traditional role of the author in most stories. Maybe how he writes in first person could be evidence for this.

I would say the big thing for you to go deeper in now is how Diaz does all these things. You have strong start with evidence, but I think you need to go further with "how." Otherwise, just add more evidence, finish your body paragraphs, and you're set! Great work.

-Lola

Wednesday, May 20, 2015

Raw Draft

Lola Lafia

Raw Draft

Due: May 21st, 2015

Raw Draft

Due: May 21st, 2015

**I am having trouble finding ways

to connect my ideas back to Diaz, so if you could keep that in mind as you read

this, that would be helpful.

Claims

(I think...)

Style changes content

Content cannot exist outside of

style.

In Diaz’s book there is no raw

truth. There are no stripped down, naked facts. There is only what he gives us,

which is his own spin on the truth. But is it reliable? Is it the truth? Can content exist outside of

style? Everybody, every author, every person, tells their tale in their own

unique way. But no matter who claims they have unbiased information, direct

records, or the truth, everything

we’ll ever see of anything will always have some sort of spin on it.

So what can we call the truth? Did

his dad really abandon his family the way Yunior claims he did? Did his mom

really disappear for a while for the reasons Yunior claims she did? Will we

ever know? Does it even matter? We have to treat his story as his own, personal

truth.

Does the way Diaz/Yunior write

about the events in his life affect our take away from the stories? Of course.

(Body

paragraphs // supppor)

- In Diaz’s book, he explores

similar themes repeatedly throughout his story. But although the content is

similar/even the same, the styles in which he explores the themes are so

different that we almost don’t make the connection. So the way he tackles his

themes hugely affects the content of the story: or at least, it affects the

effect of the content. The very first chapter of the story, “Ysrael,” revolves

around Yunior and Rafa’s encounter with Ysrael, the boy who’s face was

scratched and destroyed by a pig when he was very young, as he describes to the

reader while he watches Rafa beat Ysrael up. Eight stories later in “No Face,

we read about a boy who always wears a mask to cover up his face. And halfway

into the chapter, when we start to make the connection from story to story,

Diaz, or rather the narrator, gives us a different description of the same

event from “Ysrael.” Although the content is the same, the styles in which the

content is relayed are so different that we almost miss the connection. (***go further deeper into each of the

styles.)

- We see this cognitive dissonance (right phrase?) again even within the single

story of “Aguantando” (discuss the mom’s anticipation of papi coming, and

Yunior and Rafa’s “fantasies.”)

- Something interesting also enters

the picture when we define style,

which is most commonly done by using the idea of genres to classify writing.

Because this book is labeled as a “memoir,” we are making instant assumptions

about the story, and about Diaz himself. But would it change our reading of the

text if it was “fiction,” per se? The effect of the stories on the readers

would change, and maybe even alter our interpretation on the content and

messages of the literature. As Edna St. Vincent Millay said in 1925, “A person

who publishes a book willfully appears before the populace with his pants

down.” When sharing any of their writing with the public, authors put

themselves at stake for judgment and critique by their audience. And a book is

most reflective of the author–or at least we assume so–when it is labeled as a

memoir. So as readers, all the experiences that we see Yunior going through, we

assume they come directly from Diaz’s life. But how is it fair to place a

bounding, limiting box onto Diaz and his abilities as an author? Diaz could

very well be exaggerating things, expanding on things, adding things to help

create a sort of mood or affect. But does that break the rules and requirements

of a “memoir”? Many would argue that it does. And this shows how tricky and

restrictive it can be to place a name or category onto a style.

- Writers often run into difficulty

when trying to mimic styles. When we were told to use Diaz’s style to write our

own creative pieces, I found myself hesitant and confused out of the fear that

it wouldn’t work because our content was so different. My story had none of the

heartbreak, family drama, or immigration struggles that Diaz’s stories tackle,

and I found it nearly impossible to separate his style, his way of writing,

from his pure content.

- So it seems to be that style and

content are not counterparts or even on the same level in the hypothetical

“guide to writing” pyramid. Content is a

part of style. It is not style and content that coexist but rather form and content that fuse together to

form a style. Form is the power that we have over content; it’s our only

way of altering and influencing it. But form and content are both equal parts

of style and come hand in hand: you cannot have one without the other.

- Diaz’s way of introducing details

alters our reactions and interpretations of the events within the stories. He

has a consistent style of messing with the order of revealing information, both

with the order of the stories themselves, and even within the actual stories.

In the first chapter “Ysrael,” he welcomes us into the book by informing us of

Yunior’s familial situation and his father’s absence in his life. So when we

read chapter two, “Fiesta 1980,” it makes it all the more heartbreaking to see

their family all as one when we know they’ve had all those bumps in the

road.... (wait I just realized this doesn’t make sense because Ysrael actually

did happen before Fiesta 1980.... I’m thinking of another example but I can’t

remember it right now...)

- Diaz claims he wants to “make

some mirrors so kids like [him] might see themselves reflected back.” Although

he has the power to create this “mirror,” he portrays himself and people like

him in a way that’s seemingly negative, what with drugs, intense family issues

and scandals, and other things that would seem to reflect poorly on his

culture. But maybe this is the truth. This is his life; this is not a peace of

fiction that tries to artificially represent a group of people. Diaz is raw,

honest, and truthful, but also poetic, lyrical, and intimate. He uses the power

of style not to alter and hide the truth, but to embrace it and get in touch

with its reality.

Tuesday, May 19, 2015

Monday, May 18, 2015

Text Exploration & Dig In

Btw, I just discovered my deeper question... Does content exist outside of style?

Text Exploration

Since I'm experimenting with style versus content, I chose two passages that seem to be about the same event–they have the same content–but are written in completely different ways–they have different styles.

(Ysrael, Page 19) Rafa has just beat up Ysrael. Ysrael is on the floor, Rafa is kicking and beating him, and Yunior is just watching.

"His left ear was a nub and you could see the thick veined slab of his tongue through a hole in his cheek. He had no lips. his head was tipped back and his eyes had gone white and the cords were out on his neck. He'd been an infant when the pig had come into the house. The damage 2 looked old but I still jumped back and said, Please Rafa, let's go! Rafa crouched and using only two of his fingers, turned Ysrael's head from side to side."

The section ends.

1) Diaz writes this passage as fairly objective and description based, which is interesting because we'd normally expect there to be some more emotion // reaction for such a traumatic event like this, particularly from the narrator.

2) The OED defines damage as "loss or detriment caused by hurt or injury affecting estate, condition, or circumstances." The damage to Ysrael's face has affected his circumstances, but in fact, those circumstances have been created by other people's reactions to the damage more than the damage itself. The OED also defines it as an injury that "impairs its value or usefulness." Wow... this almost feels offensive. Is it even fair to call Ysrael's injury "damage," if that has a connotation of degradation?

(No Face, Page 157) It's the beginning of a new section; seems almost like a flashback? Clearly not from the present moment; referring to something that happened in the past.

"On some nights he opens his eyes and the pig has come back. Always huge and pale. Its hooves peg his chest down adn he can smell the curdled bananas on its breath. Blunt teeth rip a strip from under his eye and the muscle revealed is delicious, like lechosa. He turns his head to save one side of his face; in some dreams he saves his right side and in some his left but in the worst ones he cannot turn his head, its mouth is like a pothole and nothing can escape it. When he awakens he's screaming and blood runs down his neck; he's bitten his tongue and it swells and he cannot sleep again until he tells himself to be a man."

The section ends.

1) Who is the narrator here? It's not Ysrael because it refers to him in the 3rd person, but the story itself is narrated in first person because there are 2/3 times where an "I" is mentioned. Does this mean that Yunior is the narrator? If so, than the analysis of the event here in "No Face" is much deeper and more detailed and thoughtful that the description from "Ysrael." Yunior has matured a lot.

2) What is the point of this story? If it's not literally about Yunior, what can we learn about Yunior from reading this? Is Ysrael and his condition a metaphor for something deeper?

3) This style/form of conveying this information, as opposed to the style in "Ysrael," has a unique effect. It makes the reader more sympathetic towards Ysrael not only because it is more detailed, but the depth and the seriousness and the intensity of the details have increased. It also causes us to think solely about Ysrael himself, as opposed to the constant need for a comparison to Yunior that occurred in the description from "Ysrael."

Dig In

Self interview:

1) I am thinking about the relationship between style and content. I'm thinking that content cannot exist outside of style; the two come hand in hands.

2) Why? Because it's impossible to have one without the style. You can't have a style without any content to work off of, and you can't have content without implementing a style in the way you relay that content.

3) & 4) In Junot Diaz's "Drown," his stories reflect consistent and repetitive themes–after all, it is his life, and similary things often pop up. But further more, in each story, and sometimes even within each story, the content is relayed in a unique style. You may see something on page 6 and then on page 181 read something and then come back to it and realize, huh, I read about this before! But you almost missed the connection of events because the style and form in which the content was portrayed had a completely different effect on you.

5) Clearly, not only do the two work together, but style influences // affects content. In fact, I think style is actually a much broader idea. I've been referring to it as being simply the means, the medium in which content is relayed. But I think content actually falls under the category of style. Content is a part of style. There is form and content. Those are the two factors. And you can't have one without the other. So together, they form a style. Style really means form and content. They have constant and vital affects on one another.

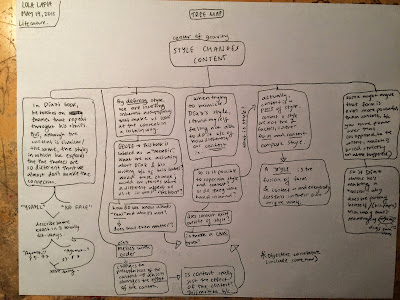

Instant Writing:

I did this in my notebook so it could be more of a flow chart, but it turned out to just be ideas all floating on a page. I think it was very helpful though, because as soon as I thought of something, I just wrote it down. It's a bit messy because I can't write as fast as I think!

Text Exploration

Since I'm experimenting with style versus content, I chose two passages that seem to be about the same event–they have the same content–but are written in completely different ways–they have different styles.

(Ysrael, Page 19) Rafa has just beat up Ysrael. Ysrael is on the floor, Rafa is kicking and beating him, and Yunior is just watching.

"His left ear was a nub and you could see the thick veined slab of his tongue through a hole in his cheek. He had no lips. his head was tipped back and his eyes had gone white and the cords were out on his neck. He'd been an infant when the pig had come into the house. The damage 2 looked old but I still jumped back and said, Please Rafa, let's go! Rafa crouched and using only two of his fingers, turned Ysrael's head from side to side."

The section ends.

1) Diaz writes this passage as fairly objective and description based, which is interesting because we'd normally expect there to be some more emotion // reaction for such a traumatic event like this, particularly from the narrator.

2) The OED defines damage as "loss or detriment caused by hurt or injury affecting estate, condition, or circumstances." The damage to Ysrael's face has affected his circumstances, but in fact, those circumstances have been created by other people's reactions to the damage more than the damage itself. The OED also defines it as an injury that "impairs its value or usefulness." Wow... this almost feels offensive. Is it even fair to call Ysrael's injury "damage," if that has a connotation of degradation?

(No Face, Page 157) It's the beginning of a new section; seems almost like a flashback? Clearly not from the present moment; referring to something that happened in the past.

"On some nights he opens his eyes and the pig has come back. Always huge and pale. Its hooves peg his chest down adn he can smell the curdled bananas on its breath. Blunt teeth rip a strip from under his eye and the muscle revealed is delicious, like lechosa. He turns his head to save one side of his face; in some dreams he saves his right side and in some his left but in the worst ones he cannot turn his head, its mouth is like a pothole and nothing can escape it. When he awakens he's screaming and blood runs down his neck; he's bitten his tongue and it swells and he cannot sleep again until he tells himself to be a man."

The section ends.

1) Who is the narrator here? It's not Ysrael because it refers to him in the 3rd person, but the story itself is narrated in first person because there are 2/3 times where an "I" is mentioned. Does this mean that Yunior is the narrator? If so, than the analysis of the event here in "No Face" is much deeper and more detailed and thoughtful that the description from "Ysrael." Yunior has matured a lot.

2) What is the point of this story? If it's not literally about Yunior, what can we learn about Yunior from reading this? Is Ysrael and his condition a metaphor for something deeper?

3) This style/form of conveying this information, as opposed to the style in "Ysrael," has a unique effect. It makes the reader more sympathetic towards Ysrael not only because it is more detailed, but the depth and the seriousness and the intensity of the details have increased. It also causes us to think solely about Ysrael himself, as opposed to the constant need for a comparison to Yunior that occurred in the description from "Ysrael."

Dig In

Self interview:

1) I am thinking about the relationship between style and content. I'm thinking that content cannot exist outside of style; the two come hand in hands.

2) Why? Because it's impossible to have one without the style. You can't have a style without any content to work off of, and you can't have content without implementing a style in the way you relay that content.

3) & 4) In Junot Diaz's "Drown," his stories reflect consistent and repetitive themes–after all, it is his life, and similary things often pop up. But further more, in each story, and sometimes even within each story, the content is relayed in a unique style. You may see something on page 6 and then on page 181 read something and then come back to it and realize, huh, I read about this before! But you almost missed the connection of events because the style and form in which the content was portrayed had a completely different effect on you.

5) Clearly, not only do the two work together, but style influences // affects content. In fact, I think style is actually a much broader idea. I've been referring to it as being simply the means, the medium in which content is relayed. But I think content actually falls under the category of style. Content is a part of style. There is form and content. Those are the two factors. And you can't have one without the other. So together, they form a style. Style really means form and content. They have constant and vital affects on one another.

Instant Writing:

I did this in my notebook so it could be more of a flow chart, but it turned out to just be ideas all floating on a page. I think it was very helpful though, because as soon as I thought of something, I just wrote it down. It's a bit messy because I can't write as fast as I think!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)